The Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans is enjoying some much-deserved attention lately. First thrown into the spotlight years ago by the HBO series by the same name, Tremé—whose full, fancy name is Faubourg Tremé (and sometimes, Tremé/Lafitte)—is finally getting the recognition it's due as the birthplace of jazz, a cultural hot spot, and a center of Black heritage.

New Orleans' Tremé Neighborhood

The neighborhood was once relegated to the position of jilted stepbrother of its better-known and flashier French Quarter neighbor to the south—even being dismissively referred to as "Back of Town"—but Tremé has more history, tradition, and architectural charm in one little acre than all 78 square blocks of the Vieux Carré combined.

Bordered by Esplanade Avenue, North Rampart Street, North Broad Street, and Canal Street (or, technically, St. Louis Street), Tremé packs a lot of culture into 150 blocks on 442 acres, or less than one square mile. The neighborhood has brought us second lines and dancing krewes, Mardi Gras Indians, and Zulu coconuts. Tremé offers authentic cooking at places including Dooky Chase's and Lil' Dizzy's Café, and it regularly hosts festivals and events, such as the Tremé Creole Gumbo Festival, Louisiana Cajun-Zydeco Concert Series, and the upcoming Tremé Fall Fest in October.

The land that Tremé has long since filled with music and life was formerly part of the Morand Plantation, as well as Forts St. Ferdinand and St. John. In around 1721, Charles Morand, working for the Company of the Indies, had built the city's first brickyard—whose bricks would be used to build some of the city's original buildings and streets. Morand soon bought that land, turning the brickyard into his plantation home. After he died, his son eventually sold the plantation to the Moreau family in 1774.

And that's when Claude Tremé came onto the scene. Tremé was a poor, white hatmaker from France who met and charmed the petticoats off Julia Moreau (whom some say was the granddaughter of the original Moreau plantation owners, while others insist that she was a freed woman, formerly enslaved on their plantation). Either way, Julia fell for Tremé's French allure and his chapeau-making ways, and the two were happily married.

Soon after they got hitched, Tremé took over the deed to the Moreau plantation. He and Julia began divvying up the land and selling off plots, primarily to both enslaved and freed people of color, including many refugees from Haiti (Saint-Domingue) fleeing the revolution there. The city snatched up the remaining land for $40,000 in 1810, and the Tremé neighborhood, which continued to be dominated by Black residents, became an official part of New Orleans in 1812.

This is how Tremé came to be one of the oldest neighborhoods in New Orleans and among the oldest African American neighborhoods in the entire country. A bit of irony: Claude Tremé, whose legacy lives on in the name of this historic Black area, was previously sentenced to five years in prison for having killed a Black man.

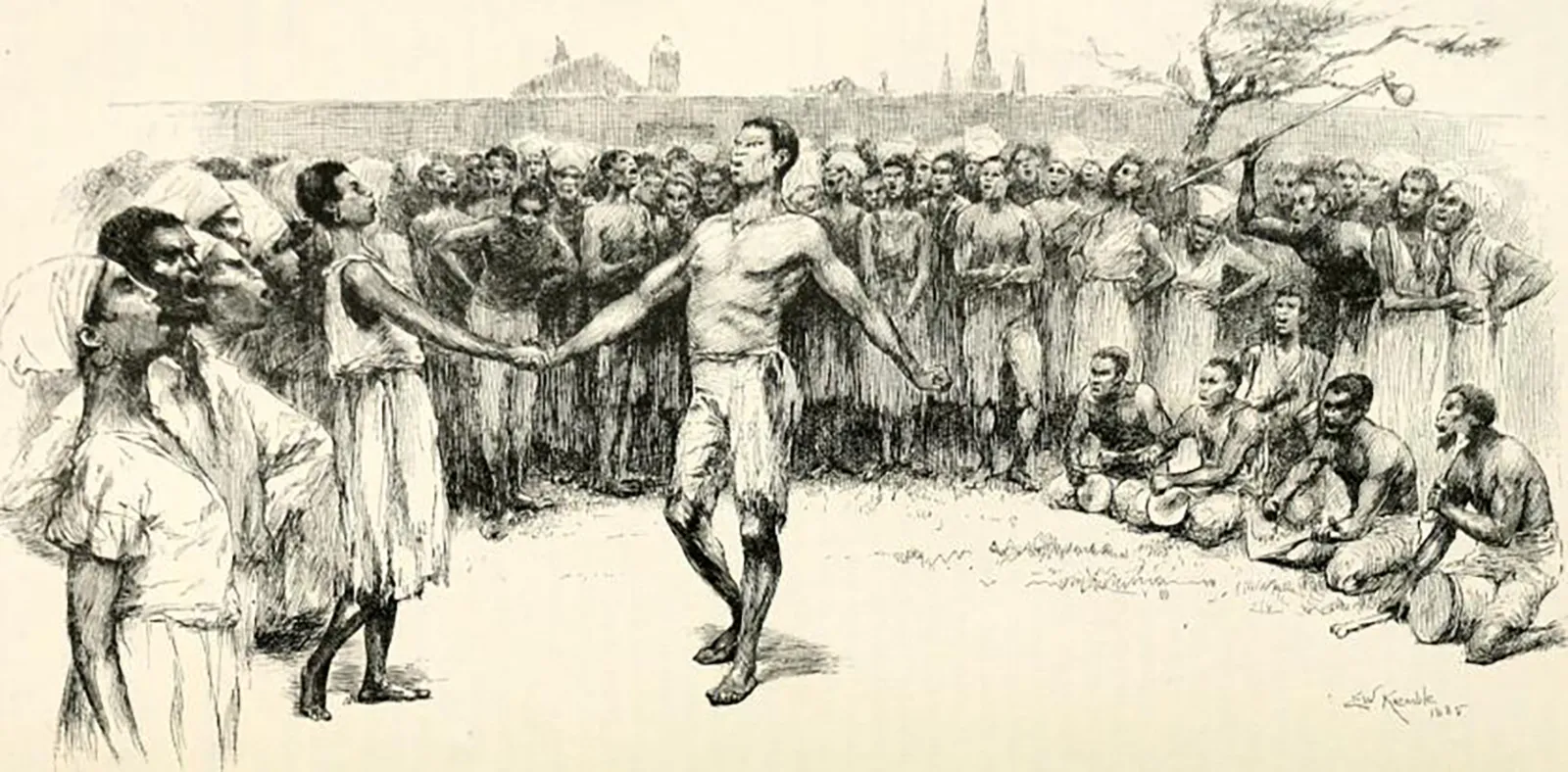

In the neighborhood's early days, Congo Square, which is now part of modern-day Armstrong Park, was developed. It was a town square that became a place for Blacks—both enslaved and free—to gather, dance, sing, and sell goods on Sundays. In fact, in 1806, a law was passed that slaves must have Sundays off to allow for such leisure activities.

Armstrong Park itself was built in the 1960s and 1970s and finally opened, some $10 million later in 1980, following an urban renewal project that destroyed 12 blocks' worth of original Tremé homes and buildings. The park was named after famous jazz great Louis Armstrong and is 31 acres of lagoons, bridges, statues, green space and buildings such as the Mahalia Jackson Theater.

But African Americans and other people of color didn't just live in the Tremé neighborhood. They also helped to build it, enrich it, and bring it to life. Black men and women provided their labor, knowledge, skills, and creativity to make the Tremé the vibrant, innovative area that it still is today. They made art and music, formed social aid and pleasure clubs, and created groups such as the Baby Doll Ladies and the North Side Skull and Bone Gang. They constructed the beautiful, historic architecture—mainly Creole cottages, townhouses, shotgun homes, and some elaborate mansions along Esplanade Avenue—that the neighborhood is known for. And they gave the area the flavor and flair that makes it unique.

There was jazz: The Tremé has a rich musical history, producing many famous musicians and at least two musical genres, including brass-band music and jazz. Musical greats such as Kermit Ruffins, Trombone Shorty, Sidney Bechet, Jelly Roll Morton, Lionel Batiste, Louis Prima, the Tremé Brass Band, and, of course, Louis Armstrong have all called Tremé home.

There were politics: Homer Plessy of Plessy v. Ferguson fame worshipped at Tremé's St. Augustine Church, one of the oldest African American Catholic churches in the U.S. and the first integrated church in New Orleans.The first Civil Rights movement in the country, which fought for Black rights in a racially charged New Orleans, is also said to have come out of the Tremé.

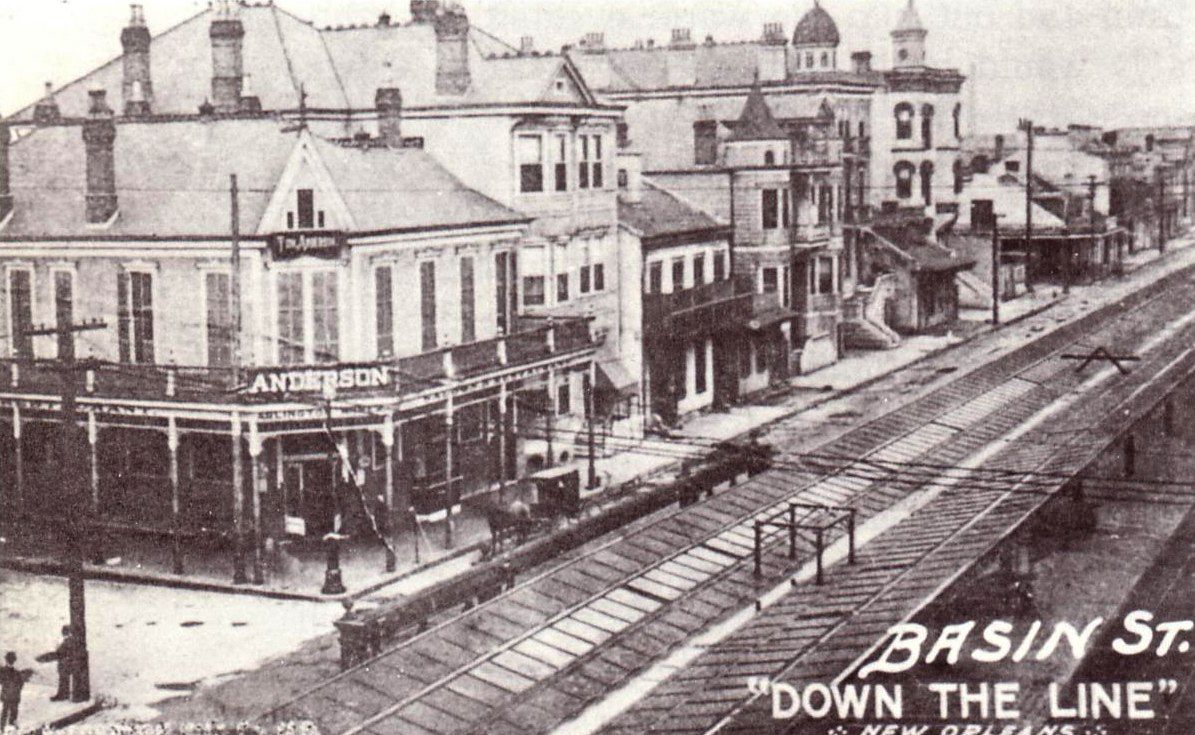

And there was sex and immorality: Tremé is the previous site of the red-light district of Storyville, the infamous area of sin and song. People went there to be entertained by the music of jazz musicians in the saloons or the company of the ladies in the (mostly) legalized brothels. Storyville was shut down in 1917.

North Claiborne Avenue used to be an active and attractive stretch of Tremé, complete with approximately 120 homes, shops, restaurants, and other businesses under the shade of hundreds of live oak trees. Then, in 1966, the geniuses of city planning decided to trade culture for concrete, leveling most of the area to make way for the giant cement slabs supporting the section of highway I-10 that now passes overhead. The construction razed a huge chunk of the neighborhood and sliced the remaining area in half.

Tremé Neighborhood New Orleans

But although they may have demolished some of the physical infrastructure of the neighborhood, they couldn't destroy the history and heritage of Tremé, which continues to thrive and reinvent itself, even under the overpass.