Because of COVID-19, more shoppers have begun turning to local butchers who source from nearby farms. What effect will this have on the meat-packing industry?

Since the early 1900s, the meat-packing industry has been fraught with problems. Plants' exploitation of workers and highly unsanitary and unsafe practices—brought to light in The Jungle, a novel by Upton Sinclair, portraying the harsh conditions and exploitation of immigrants—led to legislation that would ensure more regulations and better employee treatment. Combined with the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and the formation of labor unions, things have gradually improved.

However, even with these advancements, slaughterhouse workers in the U.S. are three times more likely to suffer serious injury than the average worker, not to mention their increased risk for mortality from lung cancer and psychological stress and trauma. Today, the rapid spread of COVID-19 among plant workers once more shines a glaring spotlight on the squalid working conditions in the meat-packing industry. Over a dozen large processors, from Smithfield Foods to Tyson, were forced to shut down temporarily, and, combined with an increase in consumer demand due to state shutdowns and stay-at-home orders, grocery store meat was not only becoming scarcer, it was far more expensive.

As the general public seems to be increasingly conscious about where their meat comes from, it should come as no surprise that, for those who can afford it, seeking out a local butcher shop that sources from smaller, nearby farms would be the natural solution.

"Our sales have definitely increased at the butcher counter," says Stephen Stryjewski, chef and co-owner of the Link Restaurant Group. "I think it's a combination of people wanting to help restaurants, and also, the cost of meat at the grocery store has gone up so exponentially that they would rather buy a better product at a similar price."

At his restaurant/butcher counter Cochon Butcher, the all-natural meats, specifically whole hogs, are sourced from Bill Ryles, who raises a cross-breed of Berkshire Blue hogs. Ryles's animals are slaughtered in a small abattoir just outside Sulfur, Louisiana, which has not been subjected to the outbreak because employees have been able to maintain safe social-distancing practices and other preventative measures.

"They're not shoulder-to-shoulder; cutting," says Stryjewski, speaking of a cramped practice that is causing the spread among workers in larger plants.

At the time of this interview, Cochon Butcher was bringing in 25 percent of sales earned before the pandemic, but the proportion of sales from fresh meats is higher than before. "That aspect of our business is taking off, regarding fresh meats and the meats we cure in-house" says Stryjewski.

At Mid-City butcher and sandwich shop Piece of Meat, owners Leighann Smith and Daniel Jackson have noticed a slight increase in sales, but due to their limited hours, it's been rough to estimate any changes. "All of our regulars came back, and then we had a big Memorial Day, but now we've kind of evened out," says Smith. "I think a lot more people are calling and inquiring, for sure."

Smith and Jackson pride themselves on the fact that they don't buy meat from any of those "big, gross farms," and, like the small farmers working with Stryjewski, Piece of Meat's source, Homeplace Pastures, has not been affected by COVID-19 outbreaks. "They treat their animals properly, and they treat their humans properly. They care about everything that's on their farm from the beginning," says Smith.

Led by Marshall Bartlett, Homeplace Pastures in Como, Mississippi, is committed to humane raising and treatment of their livestock, including the care and sustainability of the grazing land they inhabit. From raising both the animals and the food they eat to maintaining their own slaughterhouse, Homeplace Pastures, unlike many farms large and small, is the whole kit and kaboodle. Plus, most of the farm's employees live within a 10-mile radius, providing local residents with gainful employment and growth opportunities.

The owners of Piece of Meat also didn't hesitate to point out the social and political problems that aided the rise of the meat-packing and -processing industry. "As long as America keeps depressing the lower class, the factory farms will always exist, even though they mass-produce such a low-quality product," says Smith.

Widespread poverty in combination with the typical American diet is certain to keep huge processing plants in business, regardless of the detriments to the health of their employees and of consumers. "It's probably the most egregiously broken part of the food industry in the United States," says Jackson.

Kristopher Doll, owner of Shank Charcuterie butcher shop, expressed much of the same sentiment as his colleagues at Piece of Meat. "It's just a giant issue to talk about," Doll says. "You have to look at how much power the people have in Washington, and the reason they have power is because of their money. And the reason they have money is because of the volume. And the volume they have is dependent upon cheap labor, and with cheap labor, you get into some shady practices of illegal workers."

Doll also showed intense concern for how a demand for high volume has put farmers in the difficult position of slaughtering thousands of hogs per day. In order to meet that demand, hogs have to get up to slaughter weight as quickly as possible, which led to the widespread practice of using hormones and feed supplements, additives that have been known to cause health problems in consumers and, more significantly, their children. "In the 70s, when [the meat-packing industry] was running unchecked, you were getting kids in elementary school with mustaches and girls with fully developed breasts," says Doll.

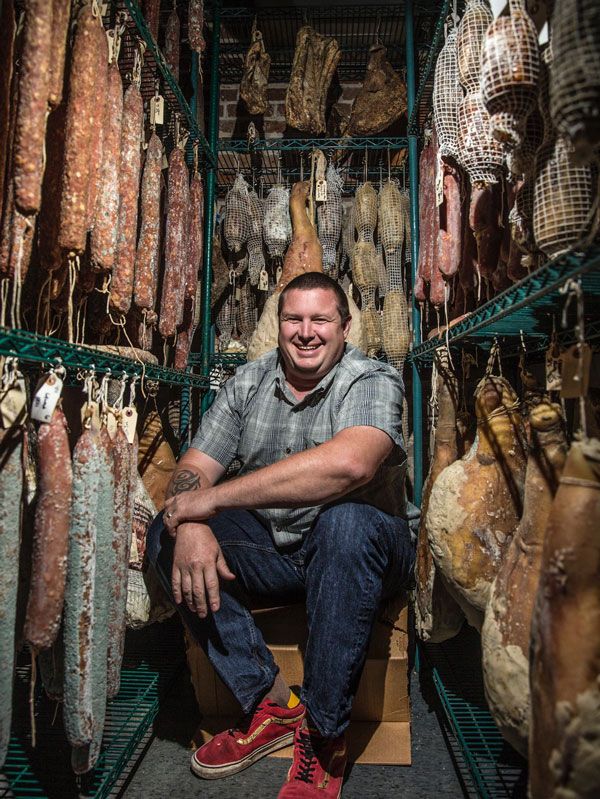

At Doll's Bywater shop, his pork and beef are sourced from Eunice Superette, an animal-processing plant committed to producing high-quality meats in a safe and clean environment. In operation for over 50 years, the Cajun-country business leases pastureland to graze its animals and does not inject hormones or excessive antibiotics to encourage growth. "I have confidence that those are good animals," says Doll."I have been to the slaughterhouse. I've been on the kill floor. I'm completely comfortable giving the meat that I sell to my kids."

Doll has seen only an incremental increase in new customers seeking quality meats, but as a longtime local purveyor (he also helped to open Cochon Butcher and Cleaver & Co.), he knows where his sales are coming from. "The hope for a specialty butcher is that the Uptown people or more affluent people in New Orleans will come in and support you," says Doll. "There are a lot of people for which it's just not economically feasible for them to buy anything but Walmart meat, and I get it. I get it 100 percent. Affordability and good meat are not synonymous."

Although restaurateur and co-owner of the Doris Metropolitan steakhouses, Itai Ben Eli, doesn't see any problem with the United States's love affair with meat, he, too, is concerned with safety and sanitation in the meat-packing industry. "I think maybe [the COVID outbreak] was a good opportunity for everybody to kind of look at the whole situation and think about how we can do this better," says Eli. "How we can manage a safer environment, a more humane environment."

Two of the three Doris Metropolitan locations, in Houston and in New Orleans, offer a butcher counter featuring their specialty, dry-aged beef, from New York strip to porterhouse steaks. Because Doris never halted its to-go operations during the COVID-19 shutdowns, they saw increased sales at the butcher counter, with both a return of regulars and some new patrons as well. Although the restaurants don't necessarily work with specific farms, they do seek out meats with the best marbling, which is, by nature, very high quality. "We always try to look back and see where our meat is coming from, and it is important to us to see that it's been responsibly grown," says Eli. "And because of the quality we seek, it's usually already a part of their system."

When talking about the mass-market meat-packing industry in the United States and all of its foibles, one must also consider the American diet. Before the Industrial Revolution (and even for some time after), meat was considered a specialty. Expensive cuts were often only found, as the main course on the tables of the rich elite, while the less expensive bits, including organ meat and other offal, were used more for flavoring dishes of vegetables, grains, and legumes eaten by the poor.

Due to the industrialization of meat-processing, now everyone can afford "good" cuts of meat, but that affordability has come at a cost. "We subsidize meat," exclaims Stryjewski. "The insane aspect of the American diet is that we don't subsidize edible vegetables."

Coming from meat purveyors, it was surprising to hear that almost all of them support the idea that, as a country, we should be consuming less meat, as opposed to more. "You don't need to eat a 12-ounce steak or a pork chop every time you sit down for a meal; it should be a treat," says Smith. "It's like an American single portion of meat is something that could feed an entire family."

Luckily for them, they also don't really see our diet changing in the near future.