"A Cajun can look at a rice field and tell how much gravy it would take to cover that much rice."

—Cajun proverb

From bayous to boudin balls, pirogues to pistolettes, zydeco to Zatarain's, Cajun culture has become an integral part of the very identity of Louisiana. You simply can't take the Cajun out of Louisiana.

Cajun culture is vibrant, historic, and multi-faceted. It's the accordion, the washboard, the two-step. It's family gatherings, fais do-dos, and catfish courtbouillon. Jambalaya, crawfish pie, filé gumbo…

The Cajuns have become so much the beloved face of Louisiana that certain aspects of their culture are regularly packaged and peddled to people everywhere, in Acadiana and beyond. The word Cajun has become a genuine brand that is tacked on to the names of food and merchandise that have nothing whatsoever to do with being Cajun, in order to increase these items' appeal. Whether it's on beer cans or snack mix bags, "Cajun" keeps turning up in the most unexpected and non-Cajun of places.

Cajun culture is also a big draw for tourists. From the music and heritage festivals, such as Festivals Acadiens and the Breaux Bridge Crawfish Fest, to the Cajun restaurants and swamp tours, hundreds of thousands of people come out annually (in a normal year) to enjoy fresh-boiled crawfish, dance to the sounds of the fiddle, and feed marshmallows to alligators from the back of an airboat.

All of this can make it very difficult to decipher what is authentically Cajun and what is just the watered-down, tourist-friendly version.

Cajuns are so much more than the beer-guzzling, gumbo-scarfing, crawfish-trapping, fun-loving, French-speaking residents of the backwoods of Louisiana that many people think they are. Their culture is based on nearly 300 years of history, community, innovation, perseverance, and tradition.

But how did the Cajun culture come to be what it is today, and how did it end up being associated with everything from a daiquiri flavor to a variety of cold cut turkey? And how much of what we perceive as Cajun really is?

Cajuns in the Beginning

In the 1600s and 1700s, still long before the French Revolution, many French people left France in search of liberté, egalité, and the makings of a better brie and headed to the New World. Some of them settled in Louisiana and set about converting swampland into Bourbon Street, while others found themselves much further north in what would later become parts of Canada, including Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. This area was named French Acadia.

The Acadians, as they were called, lived happily French for many years, raising their dairy cattle for cheese, growing grapes for wine, and cultivating grains for bread—or cake, if they chose to eat cake, with no pressure from the French monarchy either way—until the British came and ruined their fun.

In 1710, the British invaded French Acadia and demanded that the Acadians break their ties with France and pledge their undying allegiance to Britain instead. Surely not wanting to downgrade from foie gras to Yorkshire pudding, the Acadians refused. But the animosity between France and Britain continued to grow, ultimately leading to the dreadful Seven Years' War between the two countries, from 1756 until 1763. During the war, the British kicked the Acadians out of Nova Scotia and the surrounding areas in a mass eviction that was referred to as The Great Expulsion or The Great Upheaval. Although the Acadians were dispersed throughout the U.S. and many returned to France, the vast majority ended up gathering in Louisiana, in a region that came to be aptly called Acadiana, and ultimately creating the Cajun heritage that they are known for today.

Parlez-vous français?

The Cajuns had a rough go of it for a while. Not only did they have to brave the harsh conditions of rural Louisiana, but they were also often met with prejudice and intolerance by other people. In fact, the term Cajun itself originated as a shortened and disparaging form of the word Acadian.

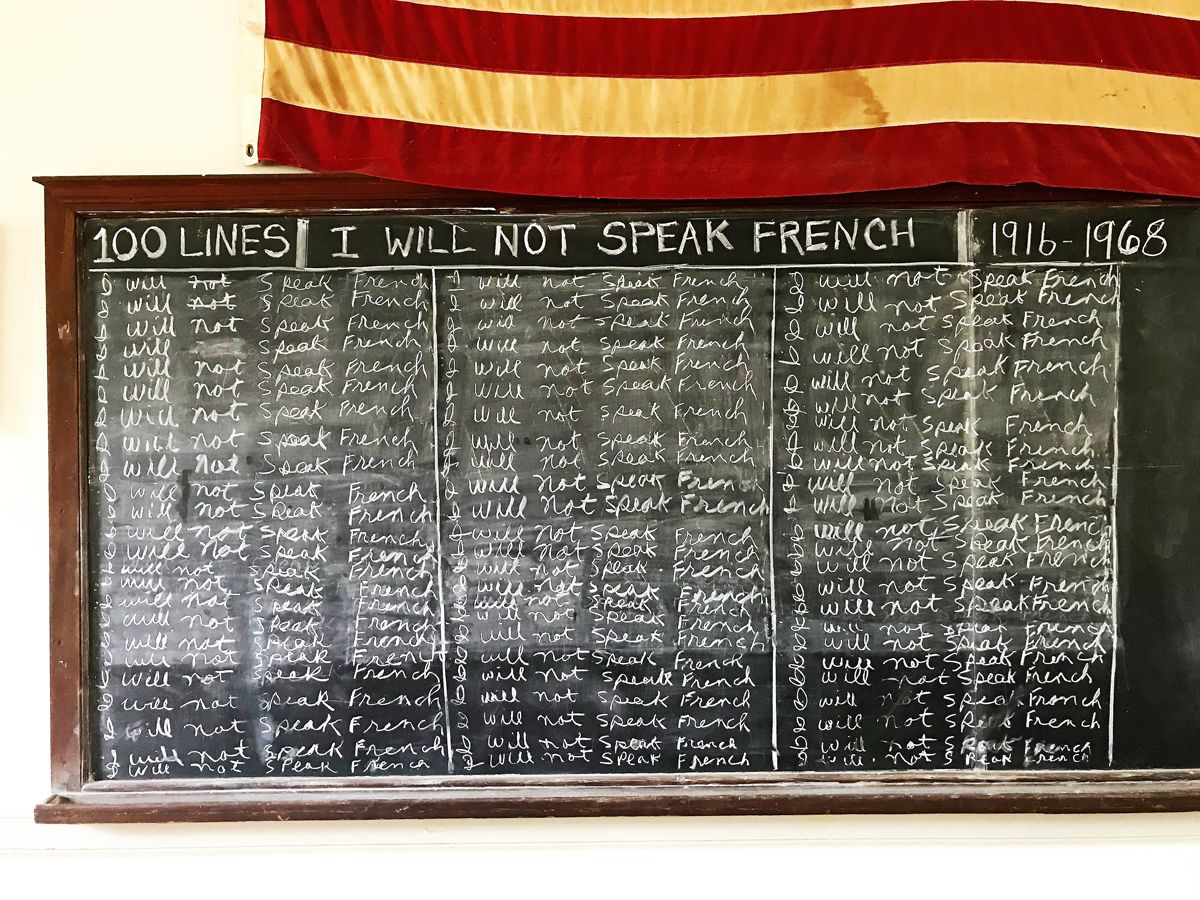

For a long time, French remained the official language of Louisiana, but that didn't last. "The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and statehood in 1812 placed serious pressure on French Louisiana to conform to the language and culture of the United States," explains Barry Ancelet, a Cajun folklorist in Lafayette. Under pressure from English-speaking authorities, the French language was slowly but forcefully removed from Louisiana. English was taught exclusively in schools, and speaking French was not just frowned upon, but eventually strictly outlawed. "Children were humiliated and punished for speaking the language of their ancestors," Ancelet says.

Philip Smith, a Cajun from Erath, Louisiana, adds, "I can remember my grandpa saying that he got disciplined—which means that they paddled him—on multiple occasions, for speaking French with his friends in school."

But while French wasn't tolerated in public, this didn't stop the Cajuns from speaking their language behind closed doors. Like so many things that are officially forbidden, speaking French never went away entirely; it just went underground. "Anytime you spoke French, it was like Prohibition—drinking alcohol in somebody's basement," says Smith.

Nevertheless, the Americanization of 19th-century Louisiana caused a multi-generational gap in French-speakers among the Cajuns of Louisiana. While this was unfortunate for the preservation of the culture, it proved to come in handy for family dynamics. Several Cajuns who were interviewed admitted that although they never learned French, it was still spoken in their presence—and they were never meant to understand.

"My parents used to speak French when they wanted to talk about private things in front of the kids," says Glen Romero (aka "Gumbo Glen"), a Lafayette Cajun. "We never knew what they were talking about. It was over our heads."

Beginning in the 1960s, the steadily diminishing Cajun French underwent an official renaissance, thanks in large part to CODOFIL, or the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana, an organization that has been successfully fighting to bring French back to Louisiana, both in schools and through various cultural events.

Cajun French is a dialect of French, but one that is somewhat divergent from traditional, standard, French French.

"Our French is slang," says Romero. "It's country French."

This is because Louisiana French was blended with other dialects, such as Creole and Haitian French, and also because Cajun French was passed down through the generations primarily as an oral tradition, unwritten, allowing for diverse spellings and usage.

The end result is a version of French that, although equally as legitimate, differs significantly from European French. The words are different. The sayings are different. The accent is different. If you say "Laissez les bons temps rouler!" to a Frenchman, or call him "Sha," he'll likely give you that "you silly American" look, as if you just put ketchup on your escargot.

Cajuns Today

While Cajun French was making its big comeback, "Cajunism" was experiencing an emergence of its own. Cajun culture was put on the map thanks to the Cajun cooking of Emeril Lagasse and Paul Prudhomme, and Cajuns have come a long way from the days when they were discriminated against and belittled. In the past few decades, Cajun culture has increased in popularity to the point that it could now be considered trendy, hip. To be Cajun has become almost a badge of honor.

"It's been popular for 25 years," says Romero. "Before that, everybody said, 'I've never met a Cajun before.' Now, you walk around, you carry your own Tabasco with you, and they know where you're from."

And yet, even while Cajun culture is having its heyday, some stereotypes still persist. Outsiders, especially those outside of Louisiana, often see only the Hollywood version of Cajuns: Bobby Boucher from The Waterboy. Evinrude in The Rescuers. Troy Landry from Swamp People.

"Most people think Cajuns are associated with spicy food and nothing else," says Romero. "Most movies stereotype Cajuns as old, poorly dressed, uneducated, and living in a cabin near alligators."

"The stereotype is that we're just backwoods, eat-the-squirrels, take-the-fan-boat-to-school, talk-in-a-dialect-that-no-one-can-understand..." says Skip Boudreaux, also a Cajun from Lafayette. "But we have paved roads, you know? And buildings."

"I think they picture somebody in overalls, maybe carrying a shotgun," adds Smith.

But what is Cajun culture, really, according to those who live it every day? What does it mean to the Cajuns to be Cajun?

One thing that everyone seems to agree on is the importance of food to the culture. For the Cajuns, food is connection. Food is currency. It's practically religion.

"Everything here is about food in South Louisiana," says Romero. "You have breakfast, you talk about lunch. You have lunch, you talk about dinner. Families get together for meals here, and it's a big thing."

"Being Cajun, to me, is family and gathering," agrees Smith. "The Cajun culture is about letting go of work, letting go of all your troubles, and we're in this moment together. And good food always makes that a better experience."

"The food's good, but it's more about the atmosphere and the socialization along with it. Crawfish boils, for example: It's not about the actual eating of the crawfish," Boudreaux explains. "It's about: You're going to someone's house, you're spending time, you're drinking beer. You stand around the pot. It's just a good time. And the food's lagniappe."

If you like to eat, it's definitely a handy thing to be in a Cajun's good graces.

Romero says that he used to work as a travelling salesman, and when his clients found out that he's from Louisiana, they'd always beg him to bring them boudin or crawfish. "So when I travelled, I'd put that in my car and bring it to my customers," he says. "Man, that's better than a bottle of scotch. Anybody can get a bottle of scotch. Not everybody can get a boudin."

Ultimately, being Cajun means good food and family. It means neighbors and community. It's friends gathering in the kitchen. Crawfish and comradery. Meals and music. It's being asked by non-Cajuns to cook, because if you're Cajun, you must be a good cook. It's enjoying what you're eating, but less than who you're eating it with. It's the Cajun joie de vivre.

"I think it's just having a unique identity that has some sort of sense of culture," says Boudreaux. "Here in Acadiana, here in Cajun culture, it's the food, it's the music, it's the Cajun French language as well. It's just all of it together that makes it something unique that you can't find anywhere else."

Ça c'est bon.