Unknown Audubon: True or False? New Orleans' Uptown Park Has a Checkered Past Hiding in Plain Sight

Here are 13 things you (probably) don't know about the most popular park in New Orleans…

1. Audubon Park was always a public green space.

Not even close! This swath of high ground along the Mississippi River was the site of Plantation de Boré, a sugar plantation owned by the first mayor of New Orleans, Etienne de Boré, before the area was even part of the city.

2. It became a park afterwards.

While the land was willed to (the then) Jefferson City as public land in 1850, it became an encampment for Confederate troops and a hospital for Union soldiers during the Civil War as the territory changed hands. Additionally, it was the site where the African American 9th Calvary "Buffalo Soldiers" were militarily activated—a monument to their achievements and military success is near the park's St. Charles Street entrance.

3. It was a park after the Civil War.

Nope...New Orleans annexed Jefferson City in 1871 and was chosen in 1884 as the site of Louisiana's first World's Fair: The World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. The event significantly helped America heal from the conflict and reinforced a sense of normalcy for business in the South.

4. After the Expo?

Yes, finally, the city deemed the 300+ acres of open green space for its people in the aftermath of the razed fair in Upper City Park, to distinguish it from the original municipal park by Bayou St. John at the end of Esplanade Avenue. After John James Audubon famously moved to New Orleans in 1881, the city officially changed the park's name in 1884 to Audubon Park to honor of the world-famous ornithologist.

5. New York's Central Park, Boston's Emerald Necklace, and Audubon Park were designed by the same person.

Not really, but close! The public parks in New York City were designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, in partnership with Calvert Vaux, in 1857-1858. Boston's meandering park system was devised between 1878-1896. But with Frederick's retirement in 1895, New Orleans retained his family's resulting landscape design firm, Olmsted Brothers, leading his sons John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. in 1898 to design Audubon Park. Because of the common sensibilities and similar eye for excellence, the Uptown park shares so many trappings and delightful surprises elemental in their father's earlier projects.

6. The park was built around the zoo.

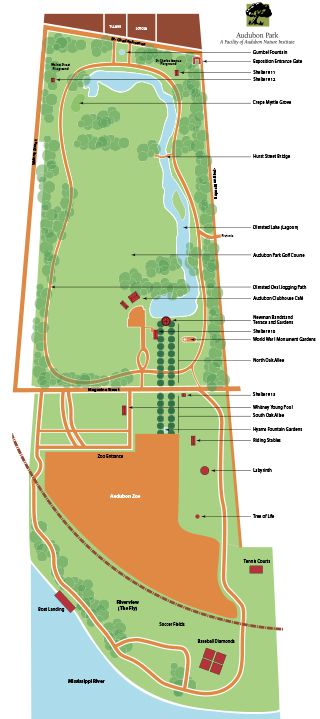

Quite the opposite. In 1916, a flight cage was added in the park. Its popularity was so strong, creation of a zoo became public demand. The creation of the Audubon Zoo spurred interest in creating other park amenities, including the Cascade Riding Stables, tennis courts, a golf course and clubhouse, baseball fields, and soccer fields to enjoy.

7. The riverfront area of the park, called "The Fly," refers to it being used as a landing area for rescue helicopters during Hurricane Katrina.

Good guess, but the area along the Riverview section of Audubon Park is believed to be inspired by a butterfly-shaped shelter along the Mississippi's bank from the 1960s. The name seems to have stuck decades after the structure was destroyed in the 1980s.

8. The golf course is not part of the original park.

It is, and it isn't…the Audubon Golf Course opened in 1898 within the park, but reduced to a Par-3 course in 2002. Park purists complained the alteration was "a desecration" of the original Olmsted brothers' intended design.

9. Audubon is the largest city park in New Orleans.

Wrong on both counts—City Park is the largest municipal park in New Orleans, and Audubon Park technically isn't even a city park! According to the Audubon Nature Institute, "Audubon Park does not receive dedicated city funding for operations and is sustained by proceeds generated by Audubon Zoo and other facilities managed by Audubon Nature Institute. To fulfill its responsibility for the improvement and long-term conservation of Audubon Park, Audubon Nature Institute is launching a focused fundraising initiative, Olmsted Renewed. The campaign supports the care and preservation of existing trees; the planting of new trees and other natural landscaping; and the maintenance of existing structures throughout the park."

10. GPS devices can find Audubon Park.

Absolutely, but if not, it has an address: 6500 Magazine St., New Orleans, LA 70118; unless you're looking for the tennis courts: 6320 Tchoupitoulas St., New Orleans, LA 70118.

11. Cars can't drive in the park.

They can if you do not include the entrances at Magazine and Tchoupitoulas Streets, along with the road around The Fly. However, cars were also permitted on the 1.8-mile loop road until they were finally banned in the 1980s and taken over by joggers, cyclists, and the occasional golf cart in search of a wayward shot off the fairway. Exposition Boulevard on the park's eastern edge is still a recorded street, but, in reality, it is simply a sidewalk address.

12. The trees are well established and just take care of themselves.

Even though they were here long before, and may very likely be here long after people in this region, these live oaks need a fair amount of TLC. Dianne Weber describe the stately collection of oak trees in Audubon Zoo and Audubon Park as "the oldest living history in New Orleans," some of which are more than 250 years old. Weber's team cares for the trees, work that includes the careful installation of lightning rods on Audubon's 150 or so historic oaks to prevent lightning-strike fires. Pest control, invasive plants, and other pollutants are also continual threats to these towering treasures shading walkways and the grand Oak Allée approach.

13. The Tree of Life is the oldest tree in New Orleans.

This may be true, but this lady's not telling her age. The massive live oak is believed to have been first planted as a wedding gift for the bride of a prominent New Orleanian centuries years ago. The gift of love still stands today as a nuptial hotspot for couples today.

ASK THE EXPERT

Audubon's Internal Communications Director Elise Amacker sheds more light on NOLA's Uptown oasis

What are some of the most common misconceptions about the park and what is the reality?

A common misconception is that the park's care and operations are fully funded by Orleans Parish taxpayer money. Though the park property is owned by the City of New Orleans, the body in charge of overseeing it—the Audubon Commission—contracts with Audubon Nature Institute, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit for its day-to-day management, including things like cutting the grass, caring for the historic live oak trees, maintaining structures like the Newman Bandstand, as well as shelters and picnic areas, trash pickup, security patrols, and more. The Commission does receive some funds for the park via the Parks and Recreation millage approved by Orleans Parish voters in 2019, but the majority of the park's care is funded by revenue from Audubon's admission-based facilities, Audubon Zoo and Audubon Aquarium of the Americas, and private donations to the Audubon Nature Institute. Community members can directly support the park's care and maintenance by making a donation to the Audubon Park Conservancy.

What is the best-kept-secret attraction or hiding-in-plain-sight aspect about the park?

The inclusive Walnut Street Playground, which was revamped in 2017 thanks to a generous donation from then Saints star quarterback Drew Brees and wife Brittany, to create a pioneering playground that offers inclusive recreational opportunities for children—and adults—of all abilities. The Walnut Street Playground promotes interactive physical, cognitive, visual, and hearing experiences for all. The unique design offers a welcoming environment for children with mobility challenges, including playground equipment accessible for people who use wheelchairs. In addition, the design presents a variety of features that provide sensory engagement and promote the development of motor skills. For parents and grandparents who face mobility challenges, the new playground is built to encourage cross-generational play, a key to building strong family ties. Examples of the inclusive playground features are wheelchair-accessible areas, including a bongo drum panel that allows fun with rhythm and tone, a Braille and Clock Panel, a Periscope Reach, a Ring-a-Bell Reach, and a bridge with guardrails. The largest playground feature is the "ZipKrooz," a two-way ride similar to a zip line, which includes a track with a bucket seat for children with limited core strength. The playground also offers conventional attractions such as slides, parallel bars, a balance beam, and tightrope bridge.

What's the most famous celebrity story involving the park?

It's too hard to pick just one! Audubon Park and Zoo are both highly sought-after filming locations for Hollywood movie and TV show productions, including features like The Curious Case of Benjamin Button starring Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett and TV shows like NCIS: New Orleans, Queen Sugar, and many more. Celebrities staying in New Orleans for filming can also be frequently spotted enjoying the park during their downtime, including movie stars like Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson when they were in town filming the show True Detective.

What do you want people to understand about the park that they need to know or do not need to know?

Unlike many cities, Audubon Park, City Park, NORDC, and the Department of Parks and Parkways are all separately funded and separately managed. That's why Audubon joined with these other "Park Partners" to create a Cooperative Endeavor Agreement tied to the new Parks and Recreation millage to find ways for all of our agencies to combine our resources and expertise to use taxpayer funding as efficiently as possible and serve all parts of our community as well as possible.

Is there a ghost or other legend in the park?

There is an urban legend in New Orleans that the large rock in the golf course is a meteorite that struck the park. It is, in fact, a large chunk of iron ore left behind from the Alabama State Exhibit of the 1884 World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition (World's Fair). The myth has been debunked numerous times but persists among New Orleans locals—and sometimes even Audubon staff.