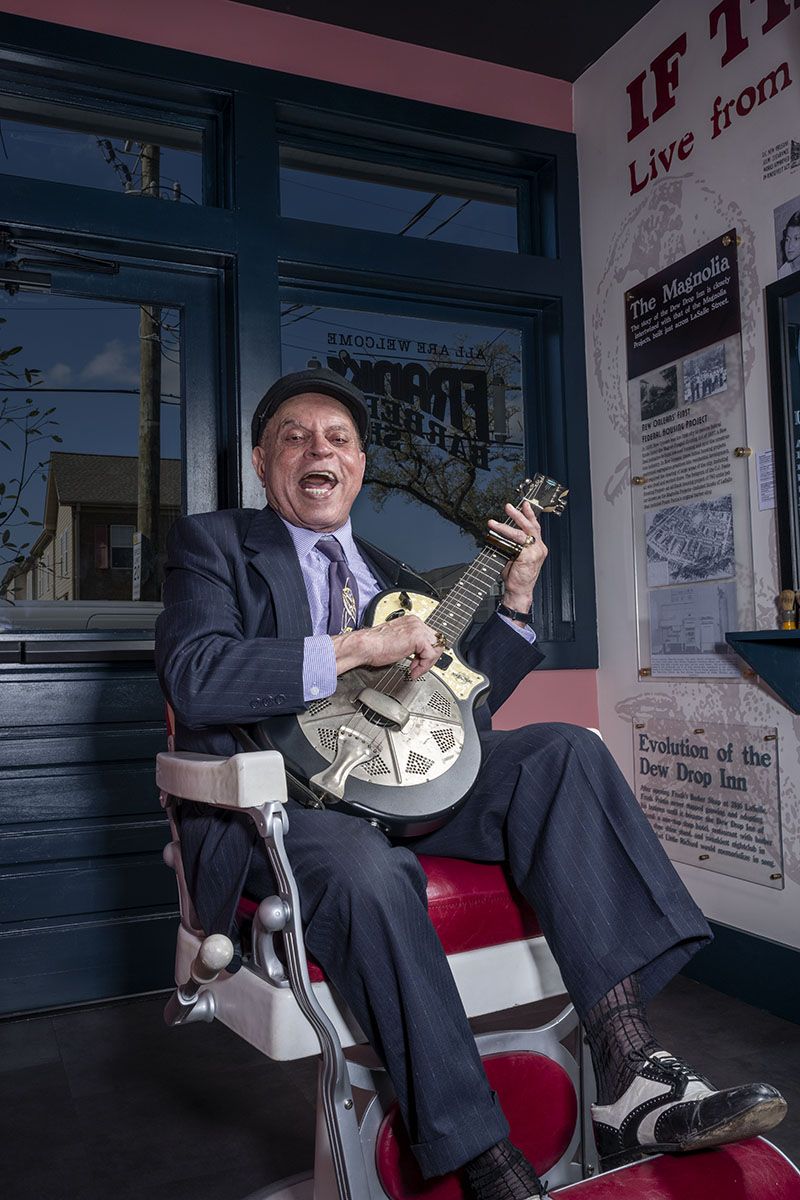

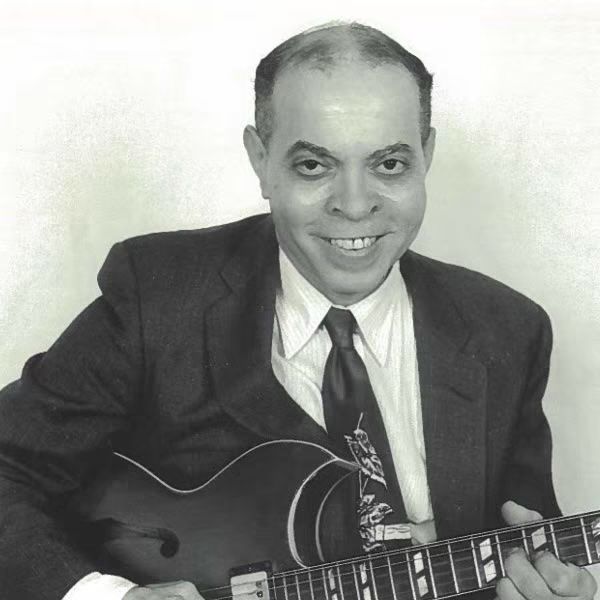

Deacon John

Saturday, May 3 | Blues Tent, 2:45 p.m.

"It ain't easy in the Big Easy," Deacon John Moore said with a wide smile and a chuckle.

Deacon John sat in the latest incarnation of the Dew Drop Inn, colorfully describing the characters and entertainers that stepped, danced, and performed on its stage decades ago. Deacon John & the Ivories were the house band there in 1960. He raved when he reminisced about the vibrant nights spent at the Dew Drop. "It was the place to go because of the stars that were traveling that couldn't frequent the white establishments. You had Ray Charles, you had Little Willie John, you had B.B. King, Bobby Blue Bland, Ike & Tina Turner, and so many others mixed with the stellar local, regional stars, and assorted cultural characters. I was in heaven because I used to hang out here, too."

Deacon John & the Dew Drop Inn

It was here that Deacon John's guitar playing talent was noticed by legendary producer/songwriter Allen Toussaint. The Dew Drop Inn was the perfect place to scout talent as its founder, Frank Pania, booked the best acts he could find. "Allen Toussaint comes up to the stage and says, 'I sure like the way you play that guitar. You want to do some recording sessions with me?'" Deacon John explained. "That was the best thing a musician could do as far as premium wages and benefits like pension money from playing on recording sessions. If you could get recording sessions, you didn't necessarily have to play as many gigs. They usually were the top-flight musicians in the city that got to play on recording sessions because they could read music and make improvisational and creative contributions to the songs being recorded."

Deacon John balanced live performance with studio sessions successfully, saying that he can brag about never needing a day job. "I've done some remarkable things with my life. I've been able to support myself entirely by my music my entire life," he proclaimed. "Not many people can say that."

From backing the likes of Irma Thomas and Ernie K-Doe to performing at a variety of functions including debutante balls and even funerals, the guitarist/vocalist's ability to adapt helped keep him in demand. "My secret was they were never able to put a label on me. A lot of the people who book entertainment would like to put you in a box. 'What is he? Is he jazz, is he blues, is he funk, is he R&B, is he rap? What category can we put him in?'" he said. "I defied categorization because I was able to play multiple markets simultaneously. I'm just good and that's all there is to it."

Though Deacon John's popularity grew, not everyone was allowed into the Dew Drop Inn to see his sets or any other shows. Segregation laws disallowed white people from entering Black establishments. Owner Frank Pania flouted "race mixing" restrictions, and he was arrested alongside some white patrons in 1952.

Deacon John said that living under segregation was "a double edged-sword." He continued, "Living under segregation, in one sense, was a beautiful thing because it had the spirit of community. It was like one big family. It had the spirit of camaraderie and community all centralized because you couldn't go to the white establishments. In another way, the division was there that you couldn't enjoy the freedoms that were supposed to be guaranteed to you by the U.S. Constitution. We had to pass laws to get our civil rights and the right to congregate."

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 officially ended segregation, though Frank Pania had to sue to totally free his venue of forced segregation in 1967. Deacon John claimed that integration contributed to the demise of the Dew Drop Inn and many other Black businesses. "Now people had other choices. They were exercising their newfound opportunities from the passage of the Civil Rights law. 'I don't want to go to the Dew Drop. I'm going to the Blue Room.'"

Deacon John & Jazz Fest

Where the Dew Drop Inn's entertainment program ended with Frank Pania's passing in 1972, the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival picked up in 1970. Deacon John proudly professed, "I'm one of the few performers alive that has played every Jazz Fest since they started in Congo Square. I played for Quint Davis' prom."

Deacon John has witnessed how well the festival highlights the city's "indigenous culture." He explained, "Through the years, there has been more and more big name entertainment, but New Orleans culture is still represented in Jazz Fest today. It's just that many of the cultural icons are no longer alive. That's what I miss most about the Jazz Fest. There's new ones coming on, but things ain't what they used to be."

As the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival has grown from a small community music fest to an international phenomenon, the Dew Drop Inn has been resurrected by Curtis Doucette to encapsulate what New Orleans music once was and to introduce the next generation of local artists—coming full circle.

Deacon John praised Curtis' work, saying as he toured the Deacon John Room at the Dew Drop Inn, "I'm so glad the right person came along at the right time to bring back what New Orleans is all about. This has an integral part in the indigenous culture. Curtis is recognizing the new talent and giving them a place where they can be heard and recognized as part of the indigenous culture and contribute to the ongoing progress of what it is now and beyond. It's a place where we can preserve and perpetuate the indigenous culture that we all love so dearly."