NOLA Architecture with History

Over a decade ago, my boyfriend and I dipped our toes into the roiling hot tub that is home ownership. We narrowed our options online and one frenetic Saturday was spent visiting three potential choices. One was a two-bedroom, one-bathroom house in the Hollygrove neighborhood on Apple Street. As we'd only ever visited the Hollygrove Farmers Market, we wanted to get a feel for the neighborhood, so we walked around a little and, after only one block, stumbled upon the Ashton Theater.

Featuring a tall, pink facade with stepped ziggurat motifs typical of the Art Deco style, as well as a bright red and yellow marquee, the small neighborhood theater first opened its doors in 1927. While hundreds of these little theaters opened up across the state, the Ashton was unique in that it was designed by Ferdinand L. Rousseve, Louisiana's first licensed African American architect.

Born in the Seventh Ward to Barthelemy Abel and Valentine R. (Mansion) Rousseve in 1904, Ferdinand's life was one filled with civil, academic, and pedagogic pursuit. Among numerous accomplishments after graduating from the Preparatory Department at Xavier University, Rousseve received a diploma in Mechanical Drawing and Elementary Machine Design from the Coyne Trade and Engineering School in Chicago, won a scholarship to MIT and ended up attaining a BA in Architecture, and was the first person to complete a PhD in only four years at Harvard University.

Although he spent many years teaching, both at Harvard University in Washington, D.C., and as associate professor and head of the Fine Arts Department at Xavier University, he also devoted himself to helping underserved communities through the Urban League of New Orleans and Greater Boston. As a licensed architect in Louisiana and Alabama, Rousseve also designed homes and buildings, many of which were located in New Orleans. Examples of his extant projects include the Central Congregational Church on Bienville Street in the Tremé, the Dr. Joseph Epps' residence on Annette Street in Gentilly, and, of course, the Ashton Theater in Hollygrove.

A little over 5,000 square feet with a balcony, the single-screen cinema was owned and operated by the Fonseca family. The Ashton Theater served the Hollygrove neighborhood for close to 30 years, showing films such as Citizen Kane and The Invisible Boy, until it finally closed in 1958.

No one bit when the building was put on the market, though the contents of the theater—including a Reproduco pipe organ with a roll frame (virtually identical to those used in Coinola coin pianos), which plays a multi-tune music roll—were later sold through an auction. The Ashton sat empty for nearly a decade until the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra purchased the old theater to use as its rehearsal hall after their former space, the St. Charles Theater, was demolished.

In 1989, local visual artist and sculptor Lin Emery purchased the Ashton and used the space to construct the massive, kinetic sculptures she was known for. Finding inspiration through nature, Emery created large-scale public artworks activated by water, wind, magnets, and motors. One of her pieces, titled Wave and is a polished aluminum kinetic sculpture poised above a reflective pool, long held a spot in front of the New Orleans Museum of Art. It now resides in the Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden in New Orleans City Park.

When Emery passed away in 2021, her son Brooks Braselman, who took over ownership of the Ashton, put the officially designated historical landmark (New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission) up for sale with hopes that its new owner would keep the building's legacy going and use the space for creative endeavors.

In the summer of 2023, local entrepreneur Janice Meredith purchased the nearly century-old theater, which she distinctly remembered from her childhood as she grew up near the Hollygrove neighborhood. Her intention was to use the Ashton in part as a manufacturing and retail space for her business selling patches and embroidered clothing, while also leaving the rest to serve as a co-working/retail space for other creative entrepreneurs.

In a NOLA.com article, Meredith said other artists would be able to book the extra space through an app called EntrepreNOLA, turning it into a "true community asset for residents in the neighborhood." She also had planned to invest $400,000 to update the HVAC system and make the structure ADA compliant. As far as can be gleaned, none of her plans for a co-working space have yet come to fruition, but, as is often said, good things come to those who wait.

As mentioned earlier in this piece, my boyfriend and I were originally looking at a house in that Hollygrove neighborhood. At that time, the Louisiana Housing Commission was offering a Soft Second program, a home-buying assistance loan that would pay up to $85,000 then. After 10 years of residency, the loan would be forgiven. A first-time home buying class and mountains of paperwork later, we suddenly found ourselves in a rush to choose a house before the program ended.

The house we looked at, originally a 500 square foot shotgun, had an addition built out front, a long living room/dining room that stepped up to a modern kitchen with dark hardwood floors throughout. The house also had a big backyard with two mature oaks and a stone brick patio.

It's funny—the house we never ended up buying on Apple Street is not often thought about anymore. More often, my mind wanders back to the daringly-Deco Ashton Theater, pondering its potential role in Hollygrove's future.

The Plaza Tower

For preservationists seeing

neglected properties around New Orleans, their inclination almost always leans

heavily toward restoration or adaptive reuse. In most cases, abandoned

structures have the potential to thrive again, breathing new life into the community.

Sometimes, a building outlives its usefulness. Maybe it's a blight, a canker on

the face of the neighborhood, and a threat to the people who live, work, and

visit our city. One such building is Plaza Tower.

Construction of the Plaza Tower began in 1964

and was completed in 1969. It was designed by Leonard R. Spangenberg Jr., a

local architect who apprenticed under Frank Lloyd Wright. Though every project

faces complications, the fate of the tower seemed doomed from the beginning.

Sam Recile, the original real estate developer who wanted to build the tower,

ran into financial difficulties and was sued by the architectural firm Leonard

R. Spangenberg Jr. & Associates for over half a million dollars in unpaid

fees. Additionally, many criticized its construction, deeming the design an

"eyesore" that detracted from the surrounding historical architecture.

In its design, Spangenberg intended to blend

modernism, expressionism, futurism, and constructivism—a failed attempt,

according to critics. In an essay published by the Society of Architectural

Historians, authors Karen Kingsley and Lake Douglas describe the Plaza Tower as

"a jumble rather than a distillation" of the modern disciplines. Since the

Plaza was built, many residents disdainfully referred to it as the "air traffic

control tower" due to its austere, function-forward design and top-heavy hat,

which was originally intended to feature a helipad.

Vocal opponents and a mid-build lawsuit

resulting in a change of ownership weren't the Plaza Tower's only hurdles. In

1965, Hurricane Betsy struck while the tower was still under construction, and

the sustained winds of over 110 mph reputedly twisted the elevator shaft, an

issue that plagued the building's elevator operations throughout its existence.

On the bright side, when construction was completed, the 45-story, 531-foot

Plaza Tower was the tallest skyscraper in the New Orleans skyline, until the

Hancock Whitney Center (formerly One Shell Square) was completed three years

later in 1972.

After the Plaza Tower was completed in 1969,

it was intended primarily as office space with some residential units near the

top. Oddly enough, very little residential space was made available. As a

result, the remaining living areas were made into offices in the mid '80s.

The multi-million dollar tower's vitality was

short-lived, serving mainly as offices for state and city employees in its

final years. In 2001, several class action lawsuits were filed against the

building's owners and managers due to a lack of maintenance, exposing tenants

to asbestos and toxic mold. Only a year later, the building was vacated en

masse and has sat empty ever since, even though the structure underwent

environmental remediation from 2008 to 2010 under the ownership of Plainfield

Asset Management.

The owners of the Plaza Tower have been many

and varied, from Giannasca Development Group and Bahar Development of Ohio (who

were temporarily successful in their $6.5 million renovation) to Plainfield

Asset Management, a now-defunct hedge fund. Bryan Burns, a partner with JSW

Plaza Tower, purchased the building in 2011 for $650,000 and had grand plans to

develop it into a mixed use space with high end apartments and commercial

space, a move that would happen in conjunction with the blossoming South Market

District on Loyola Avenue. Unfortunately, those lofty plans never came to

fruition.

In 2014, the tower was purchased by Joe

Jaeger, a local real estate developer known for buying up neglected properties

for renovation or letting them sit and deteriorate before selling them to

another interested buyer. Since Jager purchased it in 2014, the Plaza Tower has

sat untouched for over a decade.

Over the years of neglect, the

tower fell further into disrepair, and, no matter how many barriers were

erected, it became a haven for danger-seekers, graffiti artists, and squatters.

It was only a matter of time before the crumbling structure became a danger. It

began in early summer 2021 when high winds dislodged a large piece of paneling,

which fell and injured a passing bicyclist. Several months later in January of

2022, a fire broke out after witnesses reported seeing smoke coming from the

tower. Then in April of 2023, a two-alarm "trash fire" broke out on the second

floor and, only hours after the fire, police discovered a homeless man who fell

from the tower and died.

Though netting was installed

around the Plaza's crown to catch falling debris, the move was only a temporary

stopgap. In 2023, Mayor LaToya Cantrell took aim at the city's blighted

properties, levying fines against the owners and threatening demolition. Plaza

Tower definitely topped her "dirty dozen" list, along with other neglected

buildings such as the Lindy Boggs Hospital on Norman C. Francis Parkway and

State Palace Theater on Canal Street.

In 2024, the Governmental

Affairs Committee of the New Orleans City Council approved $2.7 million in

funding toward stabilization, securing the building against future accidents.

More inspiring, just this past January, a judge ruled the city can go forward

with plans to eventually demolish the ill-fated tower, a move that came after

more legal tug of war between Jaeger and the city of New Orleans.

In anticipation of Super Bowl

LIX, the city invested in beautification projects, from costly, color-changing

LED lights on the Crescent City Connection and Disney-like projections on the

St. Louis Cathedral to expansive murals on the Entergy substation and Girod

Street overpass. As demolition of the Plaza Tower obviously couldn't happen

before the football festivities, the Super Bowl Host Committee wrapped the

first 10 floors with artwork. But an artistic band-aid won't long hide the

decay that has plagued the city's skyline for decades.

State Palace Theater

Distracted by opulent Garden District mansions and dressed fried shrimp po-boys, it was a few months before I realized New Orleans is a neglected city. When journeyed beyond self-delineated safety zones, I became spellbound by the crumbling buildings, graffiti tags, and trailing vines competing to conceal grand facades and curtain broken windows.

Born and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, a metropolis with virtually no space left unsung, I found the abandoned structures in New Orleans both gloomy and alluring. Who built them? Why have they been forsaken? Will they ever be revived? This is a personal exploration of the abandoned and neglected public structures in New Orleans. This is Tumbledown NOLA.

Casey and Brandon were the first people I met when I moved here over 20 years ago. Being a decade older didn't stop the young couple from welcoming me into their city. With their guidance, I sucked and pinched my way through my first crawfish boil, spent late nights couch-bound, burning endless blunts in the Hi-Ho's backroom and early mornings gulping greasy spoon breakfasts at the Trolley Stop Cafe.

While never brave enough to accompany them, Casey and Brandon regaled me with stories of the raves they attended at State Palace, a crumbling theater on Canal Street. Though I'd enjoyed numerous beach raves in the Bay Area, I was more than a little afraid in what was still, to me, an unknown city. But their stories, and the building itself, fascinated me.

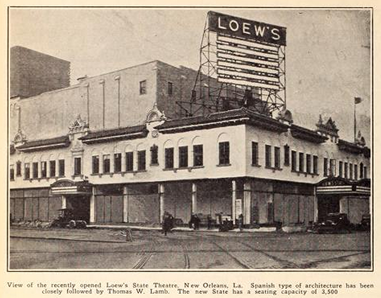

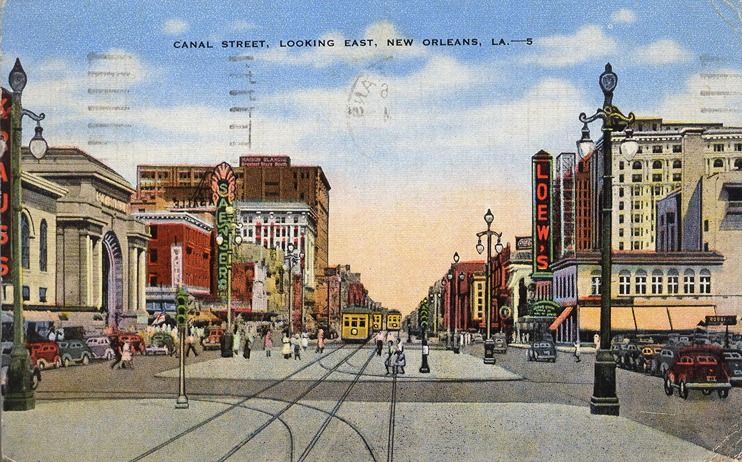

Opened nearly a century ago in 1926 with its distinctive Spanish Colonial Revival-inspired façade, The Palace was one of many Loew's Theaters popping up across the country. The Devil's Circus, starring Norma Shearer, was the first film listed on the marquee on opening night, and Marcus Loew himself appeared on stage with silent film stars Buster Keaton and Lew Cody, among others, heralding the Canal Street venue.

The Palace was designed by prominent, Scottish-born architect Thomas W. Lamb, known for the plush "movie palaces" he created for Fox, Keith Albee (RKO), and the Loews theater chains. The cinema he designed for the corner of Canal and Basin streets boasted a seating capacity for 3,335 people and a 3/13 Robert Morton pipe organ. Unfortunately, the organ fell into disuse after the early '30s with the advent of "talkies" and was later destroyed in a flood.

In the mid-70s, the theater was expanded to become a triplex, partitioned to feature two screens on the main floor while the balcony offered the third. Less than a decade later, the theater was sold to Wilson P. Abraham, a developer who planned to raze The Palace and build condominiums in its place—a plan that never came to fruition.

Rene Brunet Jr., beloved local owner of the Prytania Theater (among others) with the cinema in his blood, leased The Palace from Abraham in the late 1980s. In an attempt to bring the cinema back to its former glory, Brunet removed the partitions and opened up the balcony, uncovered the marble walls in the lobby, returned the single large screen to the main floor, and renamed the building the State Palace Theater. Along with showing classic films and television shows, the space became a live music venue, featuring performances by A-listers such as Stone Temple Pilots, Phish, and Green Day.

In the mid-90s (arguably the building's most fascinating era), the State Palace became the premier venue for raves, gaining national notoriety for its epic, wildly-themed EDM concerts featuring DJs from across the country. The late night performances were organized by local event producer James D. Estopinal Jr., aka Disco Donnie, star of the 2004 documentary film Rise: The Story of Rave Outlaw Disco Donnie. State Palace raves in their heyday included performances by drum and bass phenom Danny the Wildchild, hip hop DJ Q-Bert, Baltimore-based Charles Feelgood, and California's Bassbin Twins.

My friend Casey Sander, an avid fan of electronica and the local rave scene, recalled a State Palace concert featuring Rabbit in the Moon, a group whose style drew from house, trance, and breakbeat, and who were one of the first to mix theatrical stage performances into their acts. "I remember [State Palace] would get so packed that the walls would sweat. We wore those big-ass JNCO pants, and they would have six inches of nasty raver funk on the bottom." She also emphasized a sense of inclusivity. "No one cared at all about sexual orientation or race. Everyone was there participating together."

During the late-night raves, State Palace was split into three separate "rooms of sound." The main floor housed featured acts, the upstairs "jungle room" (an EDM genre dubbed jungle bass), and a side space they called the "chill room."

"Sometimes you could go out on the roof," recalled Sander. "I watched the sun rise from that roof multiple times." She also recalled the artistic event posters—collectible prints similar to the psychedelic, '60s era flyers for shows at the Fillmore in San Francisco.

In 1998, a 17-year-old girl attending a State Palace rave suffered convulsions from drug complications, went into a coma, and died. Estopinal and State Palace Theater became part of a nationwide federal investigation into raves and the drug culture that surrounded them. Undercover agents were sold ecstasy and LSD by attendees during several performances, but when they raided the theater, there was no evidence of drugs, just cases of water bottles, pacifiers, and glowsticks.

After Hurricane Katrina, the State Palace's basement flooded, leading to its closure. It briefly reopened in 2006, hosting its final "Zoolu" event the day before Mardi Gras, before shutting down permanently in 2008 due to fire code violations. Efforts to revive the theater began in 2014 when developer Gregor Fox purchased it, envisioning a restoration akin to successes at the nearby Saenger and Joy theaters. However, the estimated $50 million renovation price tag proved insurmountable and conflicting visions among investors stalled progress.

Fox sold the property to LC Hospitality Group, which planned to transform it into a hotel with ground-floor retail space. However, external setbacks like the Hard Rock Hotel collapse in 2019, rising interest rates, and COVID-19 delays halted these ambitions. Key proposals were also denied by the city's Historic District Landmarks Commission, further complicating the project.

As of July 2023, the State Palace is back on the market for $7.2 million. Whether this historic landmark will find new life remains uncertain. All we can do is wait and see.