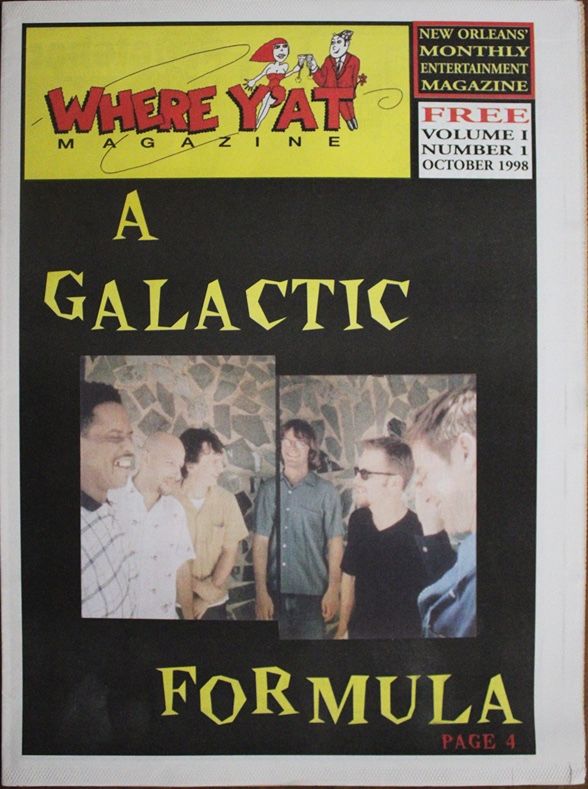

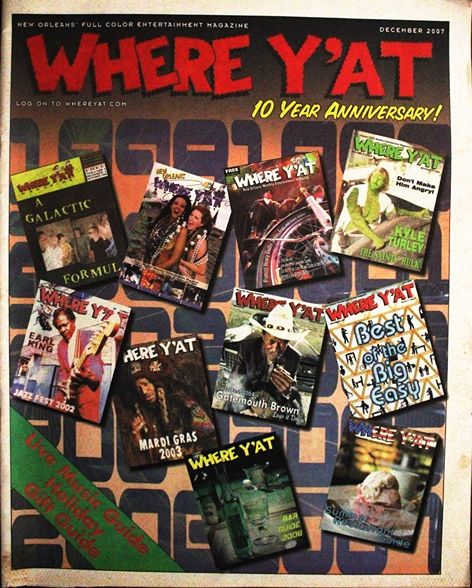

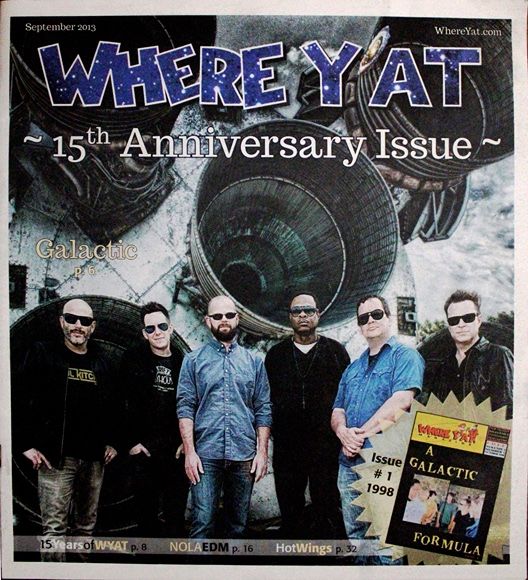

Where Y'at published its first issue in September 1998, exactly 25 years ago, with the goal of educating readers about the best of New Orleans culture in dining, nightlife, music, and the arts.

Now a quarter century out from the penultimate year of the past millennia, it is a time so vivid in the minds of many millennials that it feels like yesterday. Some things haven't changed much: a sitting U.S. President (Bill Clinton) was impeached, Apple began its conquest as the leader of cutting-edge tech with the unveiling of the iMac, and Marvel first dipped its toes into the cinematic universe with Blade (1998).

Other aspects of the past 25 years were simply unimaginable: the idea of a terrorist attack on U.S. soil (September 11, 2001), Hurricane Katrina breaking New Orleans' levees and becoming the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history (August 29, 2005), and COVID-19, a global pandemic, putting the brakes on the engine of the world (January 2020) would be considered almost as unlikely in '98 as the Saints winning the Super Bowl (February 7, 2010).

Two of these disasters, Hurricane Katrina and COVID-19, nearly shuttered the publication, now a staple of New Orleans culture.

However, it was an innovation unveiled in the early '90s that would have a far greater impact on Where Y'at's trajectory—and media as we knew it—in the years following its debut.

The Internet

Even for those who grew up in the '90s, it is impossible to fathom life before the internet. Historically speaking, the societal transformation it ignited between then and today is but a grain of sand in the hourglass of human history.

While the World Wide Web became available to the public on April 30, 1993, a majority of Americans were not using the internet—much less owned a home computer—by the end of the millennia. Twenty years later, nearly 92% of Americans not only use the internet, but carry it in their pockets—and on their wrists and in their glasses.

Compare that with the Gutenberg printing press. The first American magazines were not published until 1741, almost 300 years after its introduction in 1448. Even more shocking, national literacy rates would not equal the percentage of current internet adoption until the early 20th century, nearly a half-millennia after the Gutenberg debuted.

If the Gutenberg marks the start of mass media, then the internet may very well come to represent its finish line. Where Y'At arrived at the tipping point, one year before the web metamorphosed what a magazine was and what it had to offer.

Publishing: 1998 - 2008

Putting out an issue each month is no easy task. It is a marathon and a sprint careening towards a finish line at the end of a cliff. The tools for production, fortunately, were endless and effortless. The various pieces that make up an issue: articles, ads, photography, stock images, fact checking, and layout could be all managed from behind a keyboard.

This was not always the case. Broadband high-speed internet was not ubiquitous among the general public (i.e., the freelancers and small business owners at the heart of Where Y'at) until the mid-aughts.

"In 1998, we relied on landlines, fax machines to send ad proofs to clients, and phone books," remembers Josh Danzig, founder, owner, and editor-in-chief of Where Y'at. "Our first issues were printouts that we brought to the printer for them to scan directly and then make into plates. I have memories of our first art director, Jenny Hill, and me pulling all-nighters at the Kinko's on St. Charles and Julia printing out pages to bring to the printer in Harahan." All this added running around percolated down to the writers and photographers as well.

As a young writer working for my college's alternative weekly in 2004, I would often spend hours researching articles in our school library as wikis and search engines were still in their formative years. Likewise, social media as we know it was still a few years away—a writer had to rely on their publication's paid media directory for contacts. Just over half of Americans owned cell (not smart) phones during this time, and only 36% in '98, and those that did had very restrictive monthly minutes, so it would often be a game of phone tag for days with a subject's answering machine before scheduling an interview.

Even fewer still owned digital cameras. A basic point-and-shoot camera in 1998 cost around $1,200, and had a maximum pixel count of roughly 1 MB (less than 10x what most cell phones offer today). This meant lengthy and costly development times. Compare that to today, where smartphone photography is so advanced that iPhones have even been used to completely shoot Hollywood movies.

Looking back today, the herculean effort it took to put out a magazine in the '90s seems, well, practically medieval. Even then, many considered it an insurmountable Everest of effort. "When we started, the workers at the printer had an office pool going to see how long Where Y'at would stay in business," Danzig recalls.

Presentation: 2008 - 2014

In September of 2014, Where Y'at relaunched what quickly became New Orleans' most awarded news website: whereyat.com. Now more than just a required web presence cataloging past issues, the new whereyat.com was its own digital magazine featuring breaking news around New Orleans.

This timing was no coincidence. In 2014, print ad revenue had fallen more than 66% nationally from its peak in 2005 to its lowest point in more than 60 years. By this time, more than half of Americans owned smartphones, making print subscriptions nothing more than a carbon footprint. But the internet didn't just change where people consumed news, it also changed how they consumed it.

In The Shallows, a 2011 study of the internet's impact on our brains, author Nicholas Carr discusses how online readers showcase activity across all areas of the brain. By contrast, print readers primarily experience activity in the memory and language regions. On the surface, the web surfer may appear to have the upper hand; however, all this additional brain activity comes at a cost. The uninterrupted focus of print reading—free of videos, hyperlinks and other interactive distractions—produces greater comprehension, memory, and learning.

In less than a decade, the internet had dramatically rewired our neural-synapses and, in the process, how we ingested information. News media became keen to this. While most had already invested heavily in multimedia resources to up their online game, many whose past media du jour was print began adjusting their paper format's editorial and layout to accommodate their audience's new reading habits: headlines became punchier, graphics and visuals more prolific, and sentences shorter, spiced with SEO word-bait.

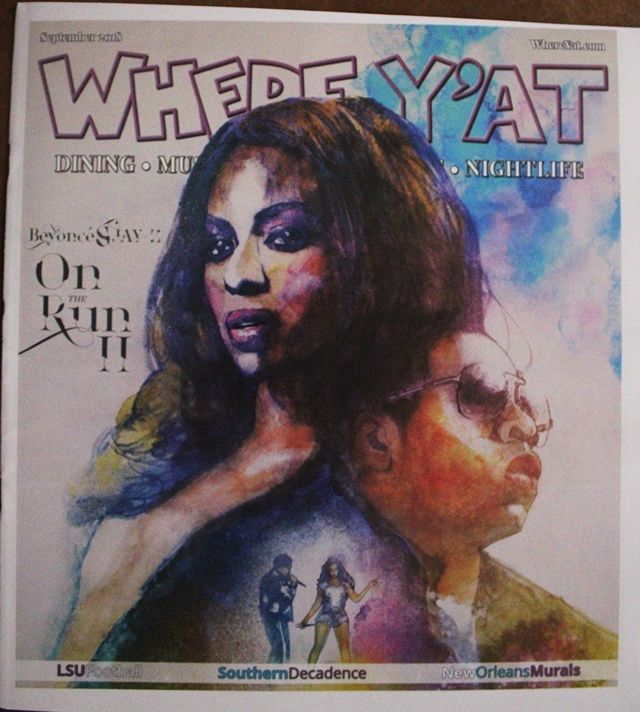

Where Y'at's monthly publication, likewise, navigated onward into these new waters. Over the coming months, the printed magazine got a make-over with more visuals, as well as its now signature glossy cover. Editorial, likewise, prioritized long-form exclusives for print, while breaking news arrived first on the web.

The internet, as McHulan predicted, not only did not leave its predecessors in peace, but in changing how we learn altogether, also proved his most famous adage—the medium is the message.

Perspective: 2014 - Present

It is suggested above that Where Y'at launched at a media tipping point. Some may argue this assessment is belated as most national media outlets had an online presence circa 1995, and online entertainment mainstays including Pitchfork ('96) and Salon ('95) had already been gaining traction for a few years. The year society began to reconsider the value of media, however, it tectonically shifted forever during the summer of 1999: the summer of Napster.

Napster was a P2P file sharing service that allowed users to download music from other members' computers. This was the first software that made, essentially, all of the world's music available in one place through the internet. The best part? It was free.

In his memoir, The Nineties: A Book, Chuck Klosterman argues Napster caused a mental transformation in consumers. " Once [they] experienced free music, they came to view music as something that was supposed to be free." Napster would be shut down after two years by a copyright ruling, but infinite alternatives—now offering video and every other form of digital media—would spawn in its place. Ten years and billions in record-label losses later, supply acquiesced to demand with the launch of Spotify.

Now, you don't need to leave your couch to access all the entertainment in the world for low-or-no cost. Thanks to COVID, even summer blockbusters now debut on streaming-on-demand for the cost of a single Saturday-night ticket, a week or two into a theatrical run.

What does this have to do with journalism? The objective of journalism, as defined by the American Press Institute, is "to provide citizens with the information they need to make the best possible decisions." For an entertainment journalist, this includes helping readers decide where to best spend their recreational time and currency.

Further disrupting the balance of traditional media in the 2000's was another scrappy startup called The Facebook. Audiences could now easily access the suggestions of like-minded "friends" rather than rely on hoity-toity critics. Users were also given a real-time, direct connection to artists, businesses, and celebrities—in essence gifting everyone press-access.

By 2014, the Pew Research Center estimates that not only did nearly three-quarters of Americans use one or more social media accounts, more than half also owned smartphones—broadcasting everything, everywhere all at once.

With the stakes so low in 2023, what is an entertainment writer's opinion worth anymore? Even Rolling Stone, the country's most iconic music magazine, ditched its ratings system this past May on the grounds that an engaged fan can "make up [their] own damn mind."

Where Y'at has flourished symbiotically in step with the new century's web 2.0 revolution. But will these competing digital disruptors eventually render its coverage obsolete?

The Next 25 Years

Because of today's digital megacosm of armchair experts and AI- and algorithmic-info echo chambers, a highly-informed, well-resourced local media presence is more important than ever. "Part of educating readers about culture is giving voice to those who create that culture," says Emily Hingle, Where Y'at Events Editor and author of Band Room: New Orleans. "You need someone on the ground who indulges in their world to fully tell their stories. Many of these web-based applications also make it hard for local artists, musicians in particular, to make a living the way they could twenty years ago. Educating the public about their struggles helps keep our culture alive."

Traditional media also remains more trusted among readers. In The Shallows, Carr references studies suggesting that due to the perceived permanence of the printed word, readers consider it more reliable than web-only media. "People don't want to know where to go to lunch—they want to know where you [locals] go to lunch", says Robert Witkowski, Creative Director for Where Y'at. "I believe this is why localized, urban lifestyle publications have largely remained unscathed as ad dollars migrated away from print over these past decades. We've been hearing about the death of print since the turn of the century, yet just this year we released our largest and most profitable issue in 25 years."

From Katrina to COVID, both New Orleans and Where Y'at have shown their amazing resilience despite the most cataclysmic of odds. And as each continues to grow and evolve in a rapidly changing, digitally intertwined world, its staff and writers will continue to deliver its mission—to bring you the best of New Orleans entertainment, music, and film reviews, and the best places to eat and party.