The New Orleans

sanitation workers wake up around 3:30 a.m. They arrive at the yard between 4:00

and 4:15, and they leave with the trucks around 5:00. They work long days,

holding onto the garbage truck as it traverses the city, doing the hard work of

hopping off, grabbing trash cans, emptying them, and hopping back on. The days

are long, and the pay is low—in fact, until a few weeks ago, it was criminally

low. The "hoppers," as they are called, are crucial to the city's function, so

their jobs didn't stop when COVID-19 hit. They were forced to expose themselves

to the virus daily, picking up trash from infected homes and healthy ones

indiscriminately. They received no hazard pay for this and, according to the

men, also received no PPE.

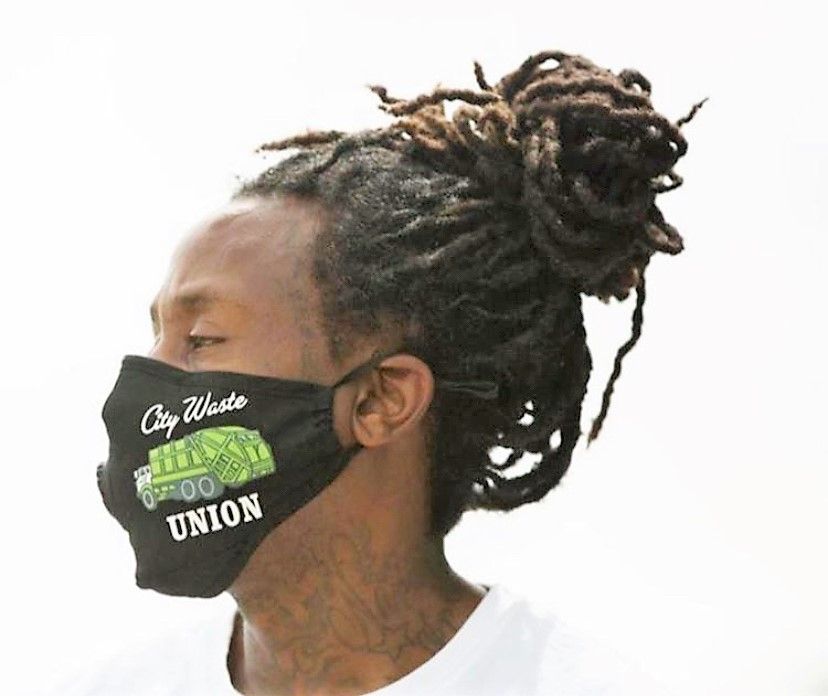

When the sanitation

workers employed under Metro Service Group decided to go on strike for a $15-per-hour

wage, hazard pay, PPE, and regular truck maintenance, they organized quickly.

They created the City Waste Union and contacted Daytrian Wilken, niece of one

of the hoppers, to serve as the union's spokesperson. They gathered support

from local organizations and set up a website

where supporters can read about their struggle and donate. They made headlines

across the country, appearing in Vice, Southerly, and The New York

Times, among others. Still, no one expected it to last over 15 weeks.

The situation is more complicated than the (already complicated) run-of-the-mill strike. Instead, it's a struggle to even pin down blame. The 14 black men on strike are employed by a subcontractor of Metro Service Group, a black-owned business. But Metro Service Group, which has increased its wages from $10.25 an hour to $11.19 as a result of the strike, is locked in a low-bid contract with the City of New Orleans. Metro Service Group says that they can't afford the $15 minimum wage, and the City of New Orleans is in a spending freeze, so it's unlikely that they'd be willing to spend more money. It's a nearly impossible situation, but, at least according to the City Waste Union, someone needs to take responsibility and make a change for these men who are providing a vital service.

Because it's a tricky

situation, the City Waste Union isn't sure exactly what's going to happen next.

They have no personal issue with Metro Service Group, especially given that

it's a black-owned business. But regardless of who is shelling out the money,

these men are doing hard labor, day in and day out, for $11.19 an hour. It's

difficult, and sometimes impossible, to make a living that way: to pay rent in

an expensive city, to provide for a family, to make it to the end of each week.

Still, there are exciting new solutions being envisioned, including the

possibility of a cooperative, where the hoppers would own—and directly profit

from—their own labor. While this sort of idea might seem far-fetched, there are

other cooperatives throughout the city, such as the Dutch Alley Artists Co-Op or

the New Orleans Food Co-Op.

The City Waste Union says

they aren't only on strike for themselves. Far from it—they're on strike for

everybody. Union representative Daytrian Wilken says, "I never knew there were

so many labor organizations that were waiting on a moment like this—for 14 black

men to stand up and say something. We realized that it wasn'tjust about our struggle; it was about

everybody's struggle. Not just hoppers, but the whole working class is

struggling. When we said we went on strike for everybody, we went on strike for

the people who have been denied healthcare, evicted in the City of New Orleans.

We were thinking about all those people

who are on the ground with us, and the system has its knee on all of our necks.

We are stuck in this constant system of oppression and poverty, and our

ancestors went through this. Martin Luther King died during a sanitation

strike. His last speech was about sanitation workers. Why are we still talking

about this 50 years later? Being on strike for everybody just meant that we're

tired. Everybody's tired. We just happen to be the ones who stood up and did

something about it."

These are powerful words

full of conviction, and that makes sense. Wilken says that the strike has taken

over her life, and she feels a class solidarity she's never felt before. She's

doing this for everybody. But at the same time, she's doing it for her family—for

her uncle Jonathan who wakes up every morning at 3:30 a.m. and hops on a truck,

traversing the city and collecting its trash. The pandemic has highlighted just

how essential people like hoppers really are to the city's function. The New

Orleans sanitation strike is just one of many voices daring to ask: Why aren't

we treating them like the important and necessary workers that they are?