Walking along Bourbon Street at any given point during the day, anyone can witness tourists, and sometimes locals alike, in a stand-off competition with revelers from second-story balconies to be the chosen ones. Once an experience reserved only for Mardi Gras has now turned into a practice that has defined New Orleans culture year-round —the catching of beads.

Historically, it's not completely certain when beads were first thrown during the parade procession, with some accounts dating back to as early as 1913. Rex, widely known as the King of carnival, changed the face of Mardi Gras by throwing strands of beads to crowds during the 1921 procession of their parade. Individual float riders on all parade processions had been known to throw different trinkets to friends or family, but, Rex formalized the practice of throwing beads with every member on the float participating.

Soon enough, all of the krewes started throwing beads—which at the time were a prized possession—at the parades during carnival season. Instead of the plastic beads that we know today, members of parading krewes used to throw the delicate Czechoslovakian-imported glass beads during the 1950s and 1960s. "I have some glass beads from my grandma," says Mariesa Barbara, the 2006 Queen of Endymion. "She said you used to be lucky to catch just one glass bead each parade."

However, as costs went up to keep importing these fragile beads, organizations switched to plastic which provided a relatively inexpensive throw to buy in bulk while catering to the large crowds drawn to the parades. Thus, the green, purple, gold, pearl, silver and pink plastic seven-millimeter-by-33-inch beads were mass produced for annual parade throws. Year after year, parade goers stacked their necks with beads of all kinds to the point where any recognizable clothing was merely seen only from the person's backside. But as the glass beads before them, these patterns began to shift as well.

"People used to brag about the quantity of beads they got, but now brag about the type of bead they got," says Tommy Marshall, who owns TJ's Carnival & Bingo Supply and has been selling beads since 1982. "It evolved from wanting quantity over quality to now wanting quality over quantity."

This reasoning may be why many krewes have begun to include their insignias and krewe crests on beads: to differentiate their krewe and their themes from all the others. This gives parade goers a unique reason to attend particular parades and to catch a little piece of their krewe and take it home with them.

A parade known for its elaborate high heels and reusable throws, the Krewe of Muses manufactures and distributes more than 30 different items, including medallion beads, with the Muses krewe logo or name every year, says the krewe captain, Staci Rosenberg. "Krewes definitely want custom designed beads," says Alyssa Fletchinger, Vice President of Plush Appeal, LLC and owner of the Mardi Gras Spot. "The [beads] used to be more generic. Now, they all want stuff with their krewe name and logo and custom items."

No stranger to the changing bead trends, Fletchinger who has sold beads in New Orleans since 1996, says she has also noticed the crowds' taste changing as well. Except to her, she's noticed a Texas-sized change in mentality that the bigger the bead, the better. "Our designs are forever changing," she says. "Now, the consumer wants a bigger shift in size to longer, wider beads."

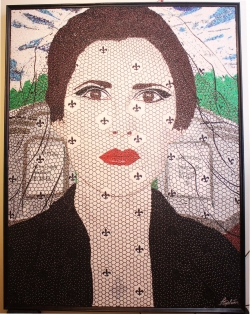

But bigger may not always be better when it comes to creating Mardi Gras beaded art. "Seed beads give depth," says artist and philanthropist, Stephan Wanger. "I'm still learning dimensions with graduation. The smaller the beads, the more depth. I don't use big beads anymore, it's a curse. It looks like a shortcut, and that's not what I'm trying to do."

Wanger moved to New Orleans from Chicago after Hurricane Katrina to help with the city's recovery. Using his background in city promotions, he started thinking of ways to help promote the culture of New Orleans beyond the volunteer work he was doing after the storm. So, concerned with the amount of refuse from Mardi Gras beads that are thrown in landfills each year, Wanger came up with a way to recycle beads while helping to raise money to promote New Orleans - Mardi Gras beaded art. "I wanted to find a way that highlighted the city the way I saw it and live a life that benefitted the city immediately," he says. "[New Orleans has] an art form here unlike anywhere else. And that is such a powerful statement."

Taking apart each individual bead and gluing them to large boards, Wanger creates mosaics of Louisiana slices of life, each with a meaning of hope and renewal. Not to mention each piece that he creates that isn't commissioned goes to a local charity, with the biggest, and perhaps record-worthy piece, going to the Make It Right Foundation, which helps rebuild the lower Ninth Ward. The artwork, titled "Skyline," features the Steamboat Natchez making its way through downtown New Orleans on a river full of signatures from anyone who stopped by to sign it. Wanger aims to get this piece in the 2012 Guinness Book of World Records for the most Mardi Gras beads put on a single amount of art.

Wanger is grateful to all those who drop off leftover beads to his gallery, Galeria Alegria, for him to use for his art; however, for those beads he can't use for his pieces, he donates them to the Arc of Greater New Orleans, who repackages and resells trashed beads to Mardi Gras krewes for use the next carnival season.

An organization dedicated to serving people with intellectual disabilities, the Arc of Greater New Orleans uses their bead recycling program to create part-time jobs for those with such disabilities to sort and repackage beads to sell for $1 a pound in 30-pound crawfish packs, says Vance Levesque, Sustainability Officer of the Arc of Greater New Orleans. What has grown from a small endeavor starting in 1994, has expanded exponentially, Vance says, going from recycling 5,000 pounds to more than 100,000 pounds of beads during the 2010 carnival season.

Levesque says the Arc has teamed up with some sponsors and supporters for some partnering events in 2012. One being with the Little Rascals parade where they will encourage people to throw beads back at their float instead of them throwing out beads to the crowds, and another being the Sierra Club, a national green environmental organization to spread the word about their initiatives. As of press time, they are also currently in talks with Phoenix Recycling and Verdi Gras to place recycling bins along St. Charles in an effort to reduce trash in Orleans Parish. "I swear, you never know what the heck is in those recycling bins," says Levesque with a laugh. "It's amazing."

Whether it's reppin' your favorite krewe or raising money for a charitable foundation, Mardi Gras beads in New Orleans have an evolving history full of bragging rights, bosoms and benefaction.

Historically, it's not completely certain when beads were first thrown during the parade procession, with some accounts dating back to as early as 1913. Rex, widely known as the King of carnival, changed the face of Mardi Gras by throwing strands of beads to crowds during the 1921 procession of their parade. Individual float riders on all parade processions had been known to throw different trinkets to friends or family, but, Rex formalized the practice of throwing beads with every member on the float participating.

Soon enough, all of the krewes started throwing beads—which at the time were a prized possession—at the parades during carnival season. Instead of the plastic beads that we know today, members of parading krewes used to throw the delicate Czechoslovakian-imported glass beads during the 1950s and 1960s. "I have some glass beads from my grandma," says Mariesa Barbara, the 2006 Queen of Endymion. "She said you used to be lucky to catch just one glass bead each parade."

However, as costs went up to keep importing these fragile beads, organizations switched to plastic which provided a relatively inexpensive throw to buy in bulk while catering to the large crowds drawn to the parades. Thus, the green, purple, gold, pearl, silver and pink plastic seven-millimeter-by-33-inch beads were mass produced for annual parade throws. Year after year, parade goers stacked their necks with beads of all kinds to the point where any recognizable clothing was merely seen only from the person's backside. But as the glass beads before them, these patterns began to shift as well.

"People used to brag about the quantity of beads they got, but now brag about the type of bead they got," says Tommy Marshall, who owns TJ's Carnival & Bingo Supply and has been selling beads since 1982. "It evolved from wanting quantity over quality to now wanting quality over quantity."

This reasoning may be why many krewes have begun to include their insignias and krewe crests on beads: to differentiate their krewe and their themes from all the others. This gives parade goers a unique reason to attend particular parades and to catch a little piece of their krewe and take it home with them.

A parade known for its elaborate high heels and reusable throws, the Krewe of Muses manufactures and distributes more than 30 different items, including medallion beads, with the Muses krewe logo or name every year, says the krewe captain, Staci Rosenberg. "Krewes definitely want custom designed beads," says Alyssa Fletchinger, Vice President of Plush Appeal, LLC and owner of the Mardi Gras Spot. "The [beads] used to be more generic. Now, they all want stuff with their krewe name and logo and custom items."

No stranger to the changing bead trends, Fletchinger who has sold beads in New Orleans since 1996, says she has also noticed the crowds' taste changing as well. Except to her, she's noticed a Texas-sized change in mentality that the bigger the bead, the better. "Our designs are forever changing," she says. "Now, the consumer wants a bigger shift in size to longer, wider beads."

But bigger may not always be better when it comes to creating Mardi Gras beaded art. "Seed beads give depth," says artist and philanthropist, Stephan Wanger. "I'm still learning dimensions with graduation. The smaller the beads, the more depth. I don't use big beads anymore, it's a curse. It looks like a shortcut, and that's not what I'm trying to do."

Wanger moved to New Orleans from Chicago after Hurricane Katrina to help with the city's recovery. Using his background in city promotions, he started thinking of ways to help promote the culture of New Orleans beyond the volunteer work he was doing after the storm. So, concerned with the amount of refuse from Mardi Gras beads that are thrown in landfills each year, Wanger came up with a way to recycle beads while helping to raise money to promote New Orleans - Mardi Gras beaded art. "I wanted to find a way that highlighted the city the way I saw it and live a life that benefitted the city immediately," he says. "[New Orleans has] an art form here unlike anywhere else. And that is such a powerful statement."

Taking apart each individual bead and gluing them to large boards, Wanger creates mosaics of Louisiana slices of life, each with a meaning of hope and renewal. Not to mention each piece that he creates that isn't commissioned goes to a local charity, with the biggest, and perhaps record-worthy piece, going to the Make It Right Foundation, which helps rebuild the lower Ninth Ward. The artwork, titled "Skyline," features the Steamboat Natchez making its way through downtown New Orleans on a river full of signatures from anyone who stopped by to sign it. Wanger aims to get this piece in the 2012 Guinness Book of World Records for the most Mardi Gras beads put on a single amount of art.

Wanger is grateful to all those who drop off leftover beads to his gallery, Galeria Alegria, for him to use for his art; however, for those beads he can't use for his pieces, he donates them to the Arc of Greater New Orleans, who repackages and resells trashed beads to Mardi Gras krewes for use the next carnival season.

An organization dedicated to serving people with intellectual disabilities, the Arc of Greater New Orleans uses their bead recycling program to create part-time jobs for those with such disabilities to sort and repackage beads to sell for $1 a pound in 30-pound crawfish packs, says Vance Levesque, Sustainability Officer of the Arc of Greater New Orleans. What has grown from a small endeavor starting in 1994, has expanded exponentially, Vance says, going from recycling 5,000 pounds to more than 100,000 pounds of beads during the 2010 carnival season.

Levesque says the Arc has teamed up with some sponsors and supporters for some partnering events in 2012. One being with the Little Rascals parade where they will encourage people to throw beads back at their float instead of them throwing out beads to the crowds, and another being the Sierra Club, a national green environmental organization to spread the word about their initiatives. As of press time, they are also currently in talks with Phoenix Recycling and Verdi Gras to place recycling bins along St. Charles in an effort to reduce trash in Orleans Parish. "I swear, you never know what the heck is in those recycling bins," says Levesque with a laugh. "It's amazing."

Whether it's reppin' your favorite krewe or raising money for a charitable foundation, Mardi Gras beads in New Orleans have an evolving history full of bragging rights, bosoms and benefaction.